Making a Head

Introduction

Coiled hand-build sculpting method: This is a rather instant method to build a head; no expensive armature needed, or laborious detaching of the sculpture from the armature at the end. It is based on hand built pottery: the process is just like building up a rather irregular rather than circular pot. The coils used don’t have to be smoothed by rolling them – and should be quite thick.

However, it means one should initially think and work initially like a “builder “ or “engineer”, rather than an “artist: develop sensitivity and understanding of how clay operates – issues like clay flexibility or hardness , weight, balance and stability of the sculpture.

By applying the “riggle test”( = gently sharing parts of the sculpture” one can assess how stable the sculpture is – and if it is not, support it with the help of external ( bottles, lids etc…) or internal supports ( barbecue sticks).

Bonding: Adding parts.

When adding new parts to your head – like nose hair, teeth – never perfectly shape them beforehand. Instead just take a rough bit of clay, bond it onto the head, and only then shape it. The reason for this is twofold: one looses a third of the shape while adding it to the main clay body; and one can judge the proportion and form better when the clay is already attached to the main body of the sculpture.

Building up the volume

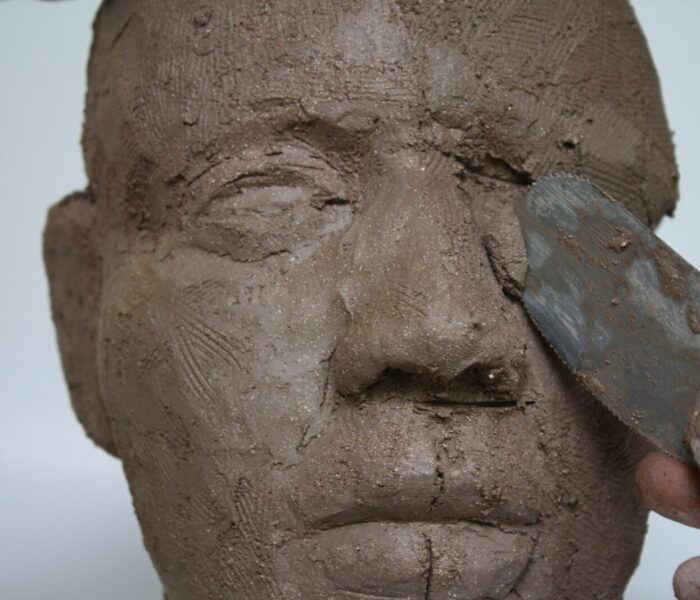

Adding clay with fingers , or with “buttering” it on with large or small tools.

- Handling Clay: Throughout the sculpting, students have to be careful not to “pinch” or “claw” the clay – but instead stroke it with a flattened hand. Pinching leads to clay surfaces becoming too thin, and therefore brittle, fragile, and likely to sag.

- Position the sculpture at eye-level – for most of the time depending on your height, you might need to raise the sculpture with the help of tins and boards; or lower your chair.

- Smoothing and modeling the surfaces: From time to time, it is a good idea to smooth all surfaces, using a kidney knife to “comb” over the entire head. Usually, the surface needs to be “straightened out”, by filling in hollows, and cutting away protrusions. Keep turning the turntable, and use the profile- line in order to look for uneven surfaces.

- “Making the moon into a balloon”: This instruction sounds so strange, that hopefully students will remember it. Craters will have to be filled in, mountains removed…. The greater smoothness of the surfaces helps to assess the form, and see the outline clearly – this is turn helps make decisions of what to change and improve. Smoothing and modelling alternates till the surfaces and lines becoming simpler and clearer. For the features to become visible, and make a strong impression, the surface around them must be clean, without interference.

Towards the end, one can model with added water on one’s hands, to make the clay softer and more responsive to the fingers.

- If water is used on the sculpture when it is still quite wet, the whole sagging –process starts all over again.

- Texture, like hair, is left to the very last, when the form and the volumes are fully defined.

1. NECK

To start with, one needs to make a first coil of clay (1) , about 1 inch thick, and lay it into a circle, like a bagel. If the coil is too thin, squash it between both hands, or add / smear more clay to it; if it is too thick, squeeze it. It does not need to be the exact length of the bagel – more clay can be added, and joined. To make the neck, 2 – 3 coils have to be laid on top of each other (1b)) .

Joining the clay coils (2/3) is crucial, both outside, and inside the neck/head; it has to be done after every coil, and cannot be saved up till one reaches half way up the head. This would be structurally unsound, and lay the foundation for future “weak points”, that will bring about the collapse of the sculpture. One can join one coil with the next by stroking downwards with four fingers, the thumb, or a tool; turning the turntable while joining can speed up the process.

A common mistake made by students is to believe that just squashing the clay parts together will join them. It only works while the clay is wet – once it dries, the parts detach from each other. Be careful to not to pinch the clay, or make the coils too thin: to hold up the whole head the clay needs to be pre-hardened and thicken the sculpture at any stage when you discover thin parts of clay – from the inside of the “pot”.

2. CHIN

To bring out the chin, the coil needs to stick out (4) at one end of the bagel; if it is a life-size head, by about a good inch, or three finger’s width. Because this is a point where sculptures often collapse later on, add extra clay and bond well (5) , where the chin meets the neck, position a plastic support holding up the chin(6), and the ensuing head that will be built upon it.

The support can be taken away in the second session , when the back head will balance the front ; and the clay will have hardened and become self supporting .

The coils don’t widen yet at the back of the head : the chin starts at the level of the back-neck; the back head (=cranium, brain) only starts curving out at the level of the nostrils – draw a line from the front to the back to locate the beginning of cranium.

Having marked out the chin (7) , mouth and nose , add a lump at the base of the face; merge it (7a) into the face. There is dimple above it , leading to he underside of the lower lip.

Keeping the head balanced: Crisis and intervention

A chin stretching out too far is often responsible for the head falling forward later on, or breaking off the neck, and sinking onto the table around it.

If the head falls over, you can widen the neck-base or change the angle of the head, by lifting up the front, and stuff (harder) clay “wedge”underneath it squeeze the whole head between both arms to lessen its bulk, change the pivotal point, and restore its balance.

If the head is breaking off the neck, or the neck is sinking into the head, you can shorten the chin, and push back the whole face towards the neck lift the chin up with one hand, and with the other hand repair the joint on the inside between neck and chin.

3. JAW

The most basic, fundamental and first proportion is to establish the jaw line, in distinction to the neck and cranium. I draw a line from the chin, along the jaw and up to the ears (two flat chunks of clay at this stage only).

Compare the width of the neck with the width of the face – seen in profile.Beware, the relationship (proportion) between them varies. A slender swan-like female neck has different proportions than a muscly gym-going young man.

Once I committed to a jaw line , I press in behind the line (8) , so that the neck recedes behind the jawbone: the neck is slimmer than the face, therefore narrower. Of I got the proportion wrong, it can be adjusted by adding or carving – as always!

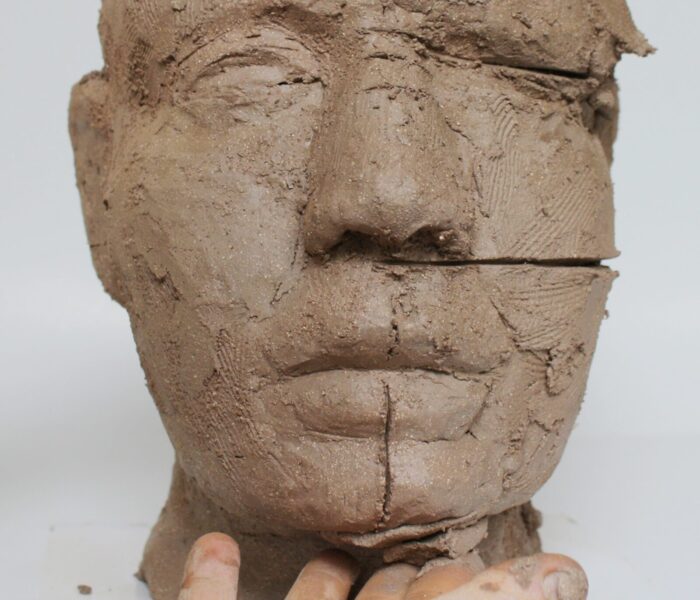

4. FACIAL PLANE

The facial plane is curved (9) – not flat . To make the face wider than the neck, pull out the clay , from inside the “coil-pot”, using the whole of your hands, even arms.Squeeze together the neck to slim it, if necessary. The facial plane is still bland – with no mouth, nose or eyes – or bone structure. However it IS curved , to allow for an evolving profile view.

At this stage you already determine the size of the future head, by establishing the first proportions (= relationship of various sizes) – neck in relation to face. If you want the head to be life-size, measure a real life face with a pair of “calipers”: width of the neck and width of the wider jaw.

The SHAPE of the face is determined by its bone structure: the jaw is less wide than the cheek bones, and so is the forehead: this accounts for the oval shape, widening most just underneath the eyes, then narrowing at the temple, slimming towards the forehead.

5.LIPS

Mark the location(7) of lower and upper lips and nose. An extra oval-shaped lump of clay ( a ”moustache”) is added between nose and mouth, to account for the “facial hill” into which the philtrum is pressed , and the round plane onto which the lips are placed..

The lower edge of this lump can be shaped with the surface of the clay-knife to already form the upper lip. The lower lip is added underneath as a thin coil of clay (10). The lips are wider in the middle, and thinner at the edge. This contrast is more marked in women. The IN-Line separating upper and lower lip is notstraight, and uneven, moving around the “lumps “ of the lips (10). The greatest challenge with lips – and the most common mistakes – therefore are the following:

- To give the lips enough volume, or roundness; one can “load” smaller tools ( leaf tool) with extra clay and apply it.

- Avoid shaping the lips though pinching, therefore creating thin and sticking out ”Donald Duck lips” the lips are “embedded in the face – at the top with the “philtrum hill”; underneath by the fatty tissues both sides of the lips contacting them to the chin area.

- Even though the lips stick out in the middle, they merge back into the face at their sides (in distinction to beaks!) the corners of the lips, merging back into the face are the hardest part : be aware of the small fold either side of the lips, that forms a “boundary”.

6. NOSE

Once you reach mid-nose. By that time, it is important to have marked the features (mouth, chin nose) in their right place drawn lines reinforced with coils of clay. But don’t get too involved yet, as their place might still change in the course of building up the head, and the proportions and location of features becoming clearer..

The basic shape is a triangle, with the nostrils being its base. The top of the nose dips slightly in from the forehead ( except for “Roman noses”) . The sides of the nostrils are lower n the face than the middle septum.

The nostrils are dug out with the fingers; they are NOT round, but instead a longish oval curve, shaped by the small “Philtrum-hill” between mouth and nose.

Common problem areas: the whole nose sticks out of the face too much, is not embedded enough in the face; or the opposite. The angle of the nose is too horizontal (“Pinocchio nose”) it is not positioned in the middle of the face (—-> “symmetry” work) the nostrils are not round, but oval , longish septum and nostrils are not long a straight line (septum= the bit between the nostril, that touches the philtrum) there is a flab of skin connect ting the nose bridge with the cheeks, half way down the nose bridge.

After another 3 coils, one reaches mid-forehead. It is worth remaining at this level for a while, in order to even out the overall shape of the head. by sculpting from the inside of the head, pressing out the clay. This saves one adding too much clay onto the head (and risking explosion in the kiln), or taking too much away (and risking holes). One can see enough of the face to judge the proportions, even if the top head and forehead is not yet done..

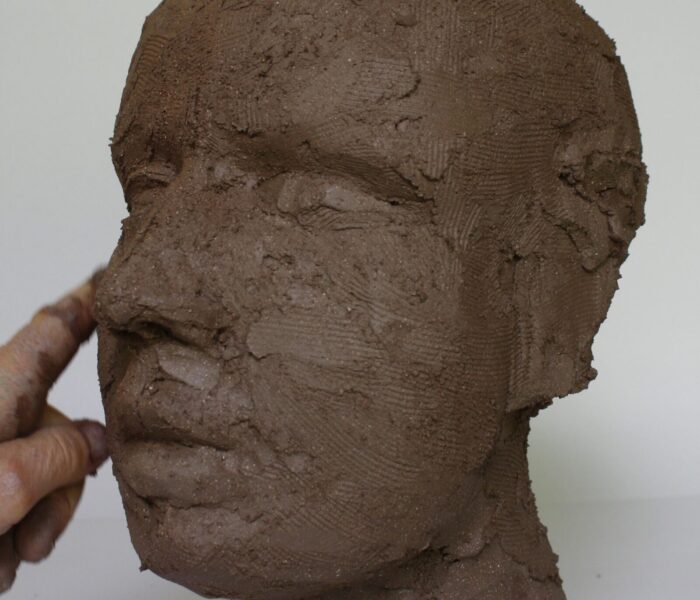

7. CHEEKS, cHECK BONE & EYES

Add extra clay to build up the cheek bones. As the nose-bridge reaches the forehead-bone, I use my thumb to dig in at either side of the nose for the eye-sockets. The bone- structure is emerging in the upper head: eyes enclosed between cheek and forehead bones. The cheekbone starts underneath the outside of the eyes, and extends diagonally down to the sides of the mouth, and up past the eyes, onto the temple, and the sides of the face.

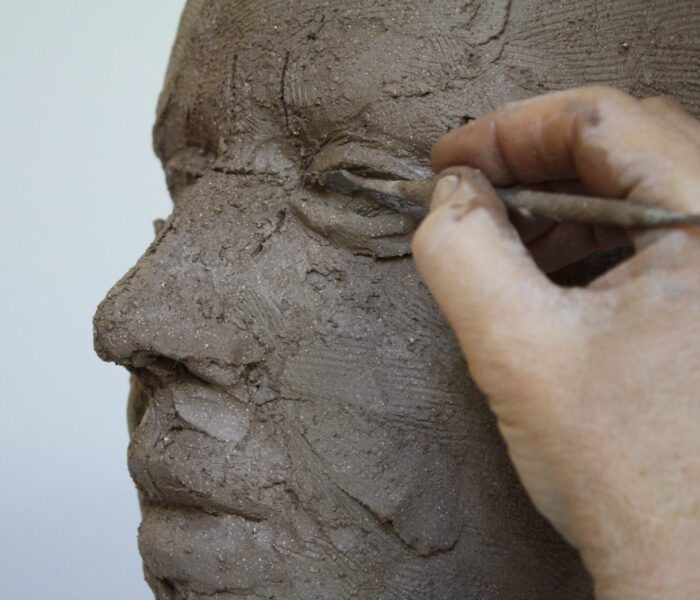

To shape these raised areas, I push the clay out from the inside of the head; or I add clay with a tool (“buttering”). It is important to create both eyes at the same level, and equal depth beside the nose. They are set deepest immediately beside the nose (bone structure is deeper and more pronounced in men), and much more shallow on the the outside.

To start with, I mark and measure the location of the eye then draw the eyes onto the clay; I place an oval mound of clay onto these incisions. Using my tool, I create round volume for the eye balls, so they become visible from the profile view: I dig deeper into the clay in both internal corners of the eyes, and less so all around; the lids emerge that way. I add a small amount of clay in the centre, to increase the protruding roundness of the eyeball.

I build up the lids with small coils, only in the middle. The lower eye lid is set deeper in the face, compared to the upper one. The lids can be created with either of two methods ( or both): the oval clay shape for the eyeball gets pressed-in around the edges – leaving behind the raised eye lids, the lids are added as coil and soaked not the clay body.

Common problem areas:

The eyes are on a straight rather than curved plane: the eye is too deep, or shallow, compared to the nose bridge. The eye is higher or lower on either side: Use a short horizontal symmetry line across the bridge of the nose to make sure the eyes are on the same level.

Solutions:

Check the view right from the top, down the forehead for symmetry of the eyes: same location, depth and plane either side of the nose – locket into the “hils” of forehead and cheekbone? check the profile view: does the eye ball protrude, are the lids curved , right depth in relation to the nose bridge?

9. CLOSING THE HEAD

Add smaller coils, that you lay on the inner side of the head, till there is only a teapot-lid sized hole left. Close this with a clay shape slightly bigger than the opening; stroke it gently side-wards for joining, don’t apply any pressure downwards, because of gravity making the head sag.

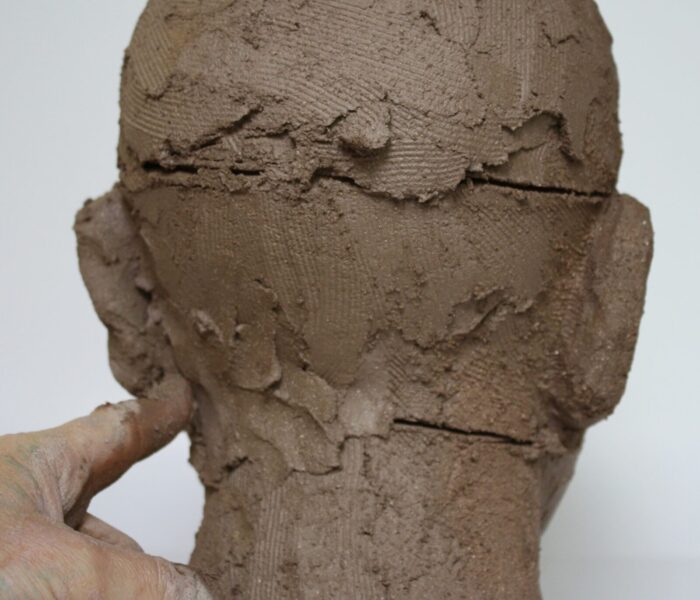

10. THE BACK HEAD-CRANIUM

The volume of the cranium is best understood from the profile view. The cranium is often larger than expected; differently: the the face slimmer than expected, and smaller part of the whole head than one thinks.

11. HAIR

Hair is created as volume , built from a slap of clay sometimes even leaving a hollow behind it to avoid too much thickness of clay hair is NOT created as not as individual hair strands.

Texture is applied to the volume later on. Hair stands out from the skin – from as little as 2 mmm, up to 10 cm for a quiff where the hair forms hollows, it might be re-created made solid in clay.

12. TECHNICAL & PRACTICAL CONCERNS

The positioning of the sculpture (13) in relation to the eye level of the student is crucial -creator and creation should look each other in the eye! This is essential to be able to project oneself onto the clay, and let it thereby come to life. This might involve raising the sculpture, or chose a lower chair. It all depends on the height of

the student.

More rarely, pick a very different view, to refresh your eye. working down from the top over forehead and nose; or looking flat down onto the face, lying on a cushion you will become more aware of the volumes, ( the “hills” in the face) the symmetry. The back head needs to be given similar importance and attention to the face. The face is the detailed, intricate “busy” part of a head; the back head is the simple, abstract beautiful surface and form (if not covered by hair). Look out for the overall line from left to right: striating with the back neck, up to the crown, and back down the face, forehead, nose mouth, chin and neck.

Mouth, eyes, forehead, and cheeks – everything in the face has an oval curve, rather than being flat Otherwise one couldn’t see the profile of the face.

13. SYMMETRY

To attain symmetry in the face, draw a vertical line down the forehead, nose-bridge, middle of the mouth and chin, and compare the two halves. To really engage with one half only, cover up the other one with a cloth or paper.

Copy over the better aspects from one side to the other. Use your fingers for rough measurements, or callipers if available. Attempt to achieve the same width, raised, lowered surface on both sides, drawing horizontal line across. To achieve over-all symmetry, the same vertical line can be used on the back head, and another horizontal line through the middle.

14. PROPORTIONS

I teach very basic proportions:the face is divided into three thirds – chin to underneath the nose, nose to eyebrows , and the remaining forehead; the lowest third is slightly bigger. Nose and mouth are slightly wider than the eyes; corner of the moth meets with the vertical line from the mid -eye.

You need to give enough attention to detail ( facial features, bone structure, hair) and refine them , in order to “recognise” the head, and respond to to the sculpture. On the other hand, you want to leave the exact location of various parts undefined till much later, and therefore not commit too much work to a facial feature.

This is especially true for making the eye (surrounded by lids) , as finding its location is so complex. Slight changes, like positioning it more right , left, higher , lower – but also deeper and more shallow each minimal adjustments has a huge impact. I often withhold making the lids till quite late.

15. OUTLINE

Because of the 3D nature of sculpture, there are 360 outlines, slightly varying – some more important than others. Frontal outline: compare central position of nose and mouth, and the right and left outlines, and their symmetry.

Every volume , seen from another angle , creates an outline. work on the outline, observing them from unusual, profile views, rather than working frontally. for instance: look from one cheek to another, across the nose, try and match the line seen from forehead over eyebrow, cheekbone to chin.

16. THE pROFILE vIEW

+ Sculpting “in the round”

It is essential to let the head grow into the third dimension, and for it not to remain a flat, frontal image. Working from various profile views will support this process. At this stage, it is worthwhile raising awareness to the curves, and the angles of surfaces.

Ask questions like: ”What is “the front” of the face, and where do the “sides” begin? How do the cheek-bones relate to this?” The forehead is a nearly straight surface, and bends round to the sides approximately at the level of 2/3 of the eyebrows. The face can become a kind of mountain range.

Forehead, nose, lips and chin sticking out, with deep valleys in-between: eye – sockets, the lines around the mouth, and underneath the chin.

17. PART OF WHOLE

Each feature is part of its surrounding region, and cannot be sculpted separately from it. The region around the mouth encompasses the folds coming down from the nostrils, the dip below the lips, and the chin.

The region around the nose encompasses the forehead, and the strips of flesh coming down to both into the cheeks, joining up with the eye-bags. The region around the eyes encompasses the eye –brows, the flesh between eye-brow-bone and eyelid, the eye-bags, and the cheekbone below its outer sides.

18. STYLE & EXPRESSION

Rather than being premeditated, this is something that should emerges as the student struggles with representing the head realistically.

Originality and inventiveness is only furthered by looking at and understanding reality first. So distortions and inventions should emerge only in the second half of the workshop. It is crucial to respond to the head in front of oneself, and take the cue from there, rather than act on preconceived intentions.

For a stylised simplified head, one might look towards African carved heads, and all the European artists inspired by them – Brancusi, Picasso etc… Planes, volumes and angles become clearer and more pronounced, proportions might be changed, or exaggerated. On the other hand , sometimes a certain expression appears “naturally” in the sculpture; it is worth empathising this, by researching more about it ( looking at at book on book so in facial muscles), to understanding it better. Look up a YouTube by Farraut on facial expression.

19. AFTERCARE

Check that the neck has not become too thick through the initial sagging process; Hollow it to 3cm thickness if necessary. Mark with initials of pupil’s names . Dry thoroughly, till very light colour. Fire slowly at C80/h up to C560, after that C120/h up to C1000

(biscuit firing ) or C1250 maximum (vitrified, ie frost resistant).

20.CREATIVE PROCESS

“Sculpting a Head”

Psychological processes – early anxieties, “key-features” and “recognition”. In the early stages of “Making a head” the student group is usually tense, with students finding it hard to get involved and “believe” in the project and themselves. After all, it seems a long way from a large a coil pot to a head…

Deep engagement with the material might well release spontaneous imagery – not-intended, unconscious images. As the facial features develop, and especially as the eyes start to “look back” at their creator, a dialogue develops – the sculpture takes”a life of its own” takes the lead, gives courage, there is less worry about future achievement, and more enjoyment and involvement in the present moment.

Self-doubt and achievement pressure fades away. When certain key features emerge on the sculpture – a lip, a nostril, hair-style students often discover that they know so much more about heads than they expected. When it comes to faces, we are all highly experienced experts.

Seemingly the head is the first shape we recognise, and are attracted to as babies – and it remains something we see and focus on constantly, in the mirror and in others we meet. ”Making a Head” draws on these half-conscious memories and impressions, and develops and activates them into firm knowledge. This remembered visual information isprojected onto the inanimate lump of clay, and one “recognises” the internal vision in the external sculpture – provided one finds a few similarities that resemble those memories.

One gains access to a vast and half-conscious store of information, which triggers near-instinctive (=unconscious , in the “flow”) responses as to what and how to change parts of the sculpture to improve the whole.

One rightly speaks in this context of a (creative) process – Through the sculpture, one makes contact with something within that one is ordinarily alienated from. Because it is un–conscious, one feels “taken over” by some unknown force, or tugged along by a gentle pull – sleepwalking with confidence, in a trance of deep, sometimes compulsive concentration. Fear of mistakes gives way to the state of “flow”, a constant process of transformation and improvements.

As a teacher, or facilitator, it it my job to create an atmosphere conducive to this kind of creative dialogue, even within a busy classroom. When things work well, it is paradoxically a social atmosphere in which everyone feels safe and relaxed enough to be

alone, involved with their work, and be able to engage and concentrate

Images

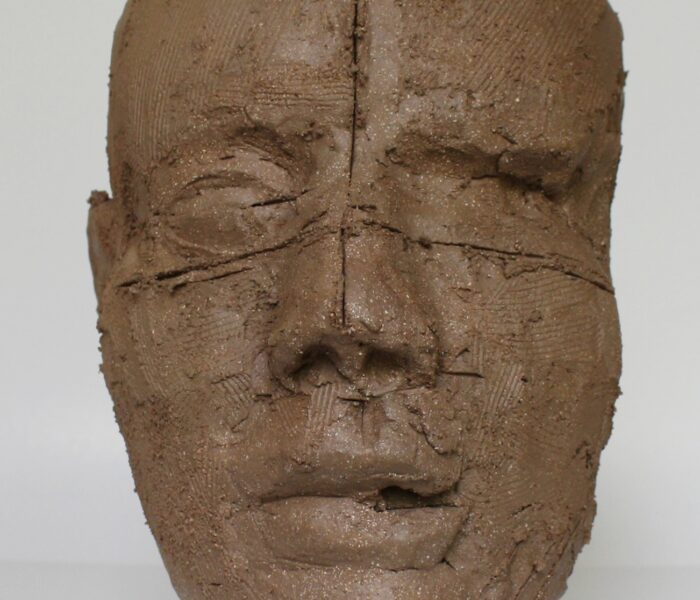

Making a half life size head

head overview

Previous

Next

head- building up the volume

Previous

Next

Head – Cheek

Previous

Next

head – Chin

Head – Lips

Previous

Next

Head – Nose

Previous

Next

Head – eye

Previous

Next

head – symnetry

Previous

Next

head – hair

Previous

Next

head – neck extending

Previous

Next

Farrut book

Previous

Next